Part 2: Organize

Convert Every Dataset Into One Uniform “Source of Truth”

The “organize” step is where you take raw datasets from hospitals, scanners, and protocols, all with different file structures and quirks, and convert them into a single standardized representation.

This representation must be:

- Easy for algorithms to consume

- Annotation-friendly

- Easy to validate with tools

Everything downstream (annotation, training, evaluation, debugging) assumes this format is correct. If “organize” is inconsistent, every later stage becomes fragile.

The Pattern That Scales: One Adapter per Dataset

One of the biggest mistakes teams make is trying to build “one big converter” that handles every dataset. It feels efficient, but it never is.

Every dataset has its own weirdness:

- Series naming differences

- Missing metadata

- Odd slice order

- Multiple reconstructions

- Broken tags

- Inconsistently compressed images

- Artifacts that only appear in one vendor’s scanner

So instead, we use a simple pattern:

Each dataset gets its own adapter

Each adapter converts raw data into a shared Uniform Data Spec, and nothing is allowed downstream unless it conforms to that spec.

This gives you:

- Modularity (new dataset doesn’t break old datasets)

- Traceability (you know which rules applied to which cases)

- Simpler debugging

The Uniform Data Spec (What You Want as Output)

The exact format depends on your toolchain, but a good uniform output usually contains:

- Standardized image data (e.g. NIfTI/H5/NPZ)

- Standardized metadata (JSON/YAML)

- Stable file naming

- Stable identifiers (patient/study/series mapping)

- Consistent coordinate conventions

- Compatibility with annotations

Example structure:

/hospital_001/patient_001/series_name/

image.nii.gz

metadata.json

ids.json

- This becomes the data everyone trusts

- This is what annotators label

- This is what training consumes

- This is what QA tools validate

Welcome to the DICOM Trap

If your input starts as DICOM (and it usually does), then “organize” is where the pain begins.

And here’s the important part:

Many DICOM failures don’t crash your pipeline. They quietly corrupt your dataset.

The three most common disasters:

1) Series Selection Mistakes

One study may contain e.g. multiple reconstructions, different kernels, partial acquisitions

Your pipeline may pick “the first series in the folder” and you won’t notice until later.

So series selection must be explicit, repeatable, and audited. First, rejection rules should be used – too small scans, not good spacing, keywords in seris name (e.g. *mip*, *oblique*, etc.). This should remove most series and what is left should be examined visually on at least a big enough amount of cases. This should help in policity choosing – is randomly taking from what is left is good? Is manaul picking is needed for every case? Are more automatic rejection rules can be used?

2) Orientation Flips and Axis Confusion

Everything looks fine… until you overlay a mask and realize:

- Left-right is mirrored

- Superior-inferior is swapped

- Slice order is inverted

This gets especially nasty when mixing DICOM to NIfTI converters and annotation tools that each interpret orientation slightly differently.

The fix isn’t clever code. The fix is validation.

3) Spacing Inconsistencies

Sometimes DICOM spacing tags:

- Disagree with slice positions

- Are missing

- Are wrong (yes, wrong)

Your model might still train, but measurements and derived features become meaningless.

And in medical AI, meaningless measurements = meaningless model.

How to Validate Organize (Without Going Insane)

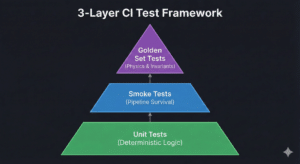

You validate it in layers.

Layer 1: Automated sanity checks

Per-case:

- Correct shape/dimensions

- Spacing is positive and plausible

- Orientation matches standard

- Intensity range is plausible

- No duplicate slices

- Required metadata exists

Per-dataset:

- Distributions of spacing, shapes, intensity stats

- Fraction missing tags

- Corrupted/skipped case count

- Duplicates by hash

- ID collisions

This catches “hard failures.”

Layer 2: Visual inspection workflow (random sampling)

Automation doesn’t catch everything.

So you do the human thing:

- Sample random cases

- Open in viewer

- Scroll

- Verify anatomy direction

- Compare against metadata

This is how you catch “it looks plausible but is wrong.”

Trust the automation – but verify the visuals.

Layer 3: Traceability is validation

Every organized output should record:

- Where it came from

- What rules were applied

- What was skipped and why

A dataset pipeline without traceability is like a lab notebook without dates.

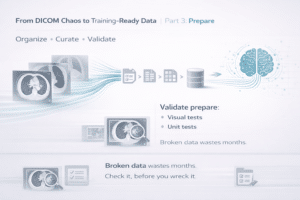

Next: Part 3 — Prepare: Turning Organized Data into Training Artifacts Without Creating Silent Bugs